Archaeology Update for the Week of January 23

Hello there, everyone. It’s that time again! Another week of excavation is behind us and I hope you all are enjoying the updates. Did anyone see the Blood Moon over the weekend? It was cold out there, but we did!

This week, the crews continued to work mostly within Block A after we had the water main break next to Block C. Despite some heavy winds over the weekend that left the beautiful (and incredibly helpful) Block A tent a crumpled heap, the crew has been able to get a lot done!

Block A is actually about 50 feet to the left of the edge of this photo…

View of the different layers of burned rock features we are encountering within Block A.

Excavating through and adjacent to Feature 62, in the bottom (so far) of Block A.

Time lapse video of the archaeology crew working in Block A.

Animal Bone is Coming Out of the Lower Depths in Block A – Bring on the Faunal Analyst!

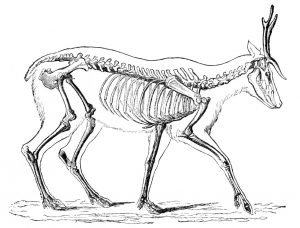

Last week, we mentioned the likely deer mandible that was recovered in the lower depths of the unit. The more test units we excavate at this same depth, the more animal bone we seem to be recovering. Animal bones give us a great deal of both cultural and environmental information, so that’s exciting, because they can not only shed light on food preferences and cooking practices (assuming these animal bones are indeed from prey; some species may well be scavengers or pets or something else), but they can tell us about habitation and hunting ranges, climatic conditions (animals tend to migrate with preferred climate), and – in some cases – even seasonality.

View of the likely deer mandible fragment recovered from Block A.

As an example of the latter, if the archaeologists were to recover a large number of white-tailed deer bones from fawns (I know, it’s a little sad, but bear with me), we know those are typically born in the Spring and Summer months. These bones could then be projected to have come from a hunt in the Summer. If they were present amongst the assemblage, fawns’ mandibles will exhibit tooth development and eruption patterning that can refine that time window even more. We could then look at other artifacts from the same horizon to begin to piece together what these people might have been doing during this particular period of a given year.

When archaeologists do recover animal bones (archaeologists typically call them “faunal remains”), specialists who are called faunal analysts study the bones to gather distinct information that is useful to archaeological studies. Some people call this work “zooarchaeology.” I’m sure there’s some difference in the terms, but the two are pretty-much the same. Many of us archaeologists, myself certainly included, are not much good beyond seeing a bone and saying, “Yep! I’m pretty sure that’s a bone…” (ok, maybe we’re a little better than that, but not much). We rely on these specialists to tell us what kind of animal a particular bone came from and what part on the animal it came from. Sometimes a species identification isn’t possible but they can at least tell us something. For instance, a bone fragment might be so small or in such poor condition they can’t tell for sure if a bone is from a bison, but they can confirm it’s from a large mammal. They work with a broad range of species from mammals to birds to fish to reptiles and amphibians. Many of these faunal analysts have type collections composed of the bones of different known animals they can refer to if they aren’t sure.

In addition to identifying what type of animal(s) are there, faunal analysts give us some suggestions on how many of those animals made up all of those bones. They identify a “Minimum Number of Individuals” or MNI as it’s commonly called by looking at all of the bone fragments and finding how many fragments have pieces that overlap others. Let’s use a human as a more familiar example of identical phenomena with animal bones. Humans – under most circumstances – only have one distal phalange on the thumb of their left hand. “Phalange” is the medical name for a finger bone and “distal” is a term used to define whether something is closer (“proximal”; think “proximity” or “approximate” meaning “pretty close”) or farther (“distal”; think “distant” meaning “farther away”)from you. So the distal phalange in this example, is the farthest-out finger bone on your thumb; the one that goes up and down when you thumb wrestle).

If we found two of those same bones in a larger assemblage of other bones (or two pieces that overlap one another), one person couldn’t have two of them, so that would mean there had to be a minimum of two individuals that compose all of these bones. There could be more (there’s no rule that an individual skeleton has to have a preserved left distal phalange from the thumb… obviously!), but it’s a safe bet there can’t be less. Therefore, that’s the so-called “Minimum Number of Individuals” in that example. You can work through all of the bones and begin to find other areas where distinct bones overlap and you can build on your interpretations.

But remember: be sure to use “MNI” – you’ll be using the lingo we use, which I guarantee will impress your friends.

The Shoring Should be Delivered for Block D This Week and Block C is Getting a New Cover

Since excavations in Block D have gone so deep, we need to be sure that our archaeologists are safe as they keep going even deeper. To make sure of that, a bracing system, called “shoring” will be installed in Block D today. These will be large, telescoping bars that will push hard against the excavation block walls to keep it from caving in. Safety always first…

A similar, but much larger example of the type of shoring that is going to be installed within Block D. This is from a large excavation of a site within Zilker Park in Austin.

And over in Block C, our good ol’ fickle friend, Mindy has been working hard figuring out a new cover that will hopefully keep things dryer than they have been. We just need to find a big tarp, though.