Prehistoric Background

Located on a natural terrace at the confluence of a perpetually-flowing natural spring and an adjacent creek, the Headwaters property would have been prime real estate for anybody, from the earliest days of human occupation all the way up to today. Our research at this site indicates that people have lived here for at least 8,000 years but more detailed investigations could very likely extend that timeline even farther into the past, possibly even to some of the earliest archaeological sites in Texas and the United States.

As you learn about this site, it’s important to have some background on what we know about the 13,000+ year history of people living here in Texas and in Central Texas in particular. It turns out that this area is among the more archaeologically-rich in Texas. Archaeological data indicates that Central Texas hasn’t been popular just for the last couple decades; it’s been popular for as long as people have lived in the New World. And why is that? One big reason is its unique natural setting. Three distinct ecological zones converge right here along a line that generally follows the modern-day I-35 corridor. To the west is the Hill Country and Edwards Plateau. To the east is the deep, flat, fertile clay of the Blackland Prairies, Cross Timbers, and Post Oak Savannah. And to the south is the South Texas Plains region. Someone living where these zones all come together has ready access to distinct resources like food and raw materials available to each zone. Human culture-wise, this place is special – and we aren’t even including the barbecue!

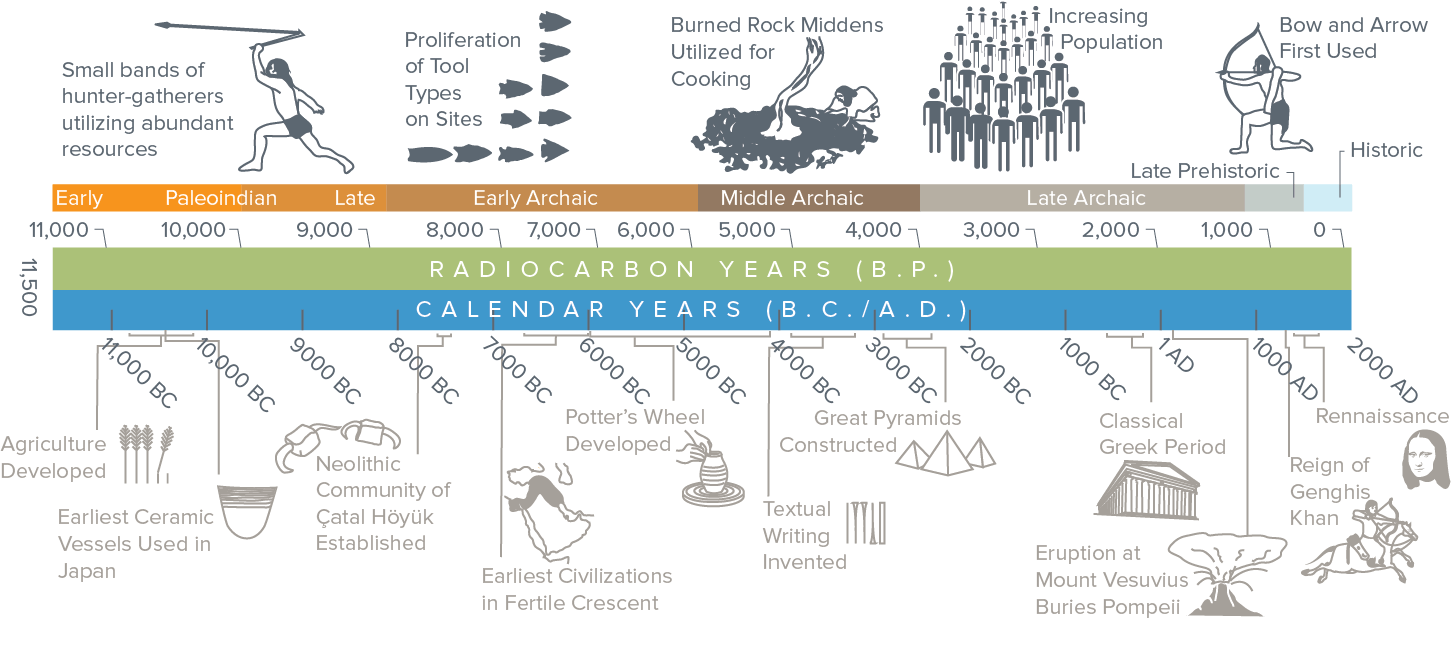

Archaeologists typically break Texas prehistory into four major chronological groups: Paleoindian (11,500-8800 years before present ), Archaic (8800-1200 B.P.), Late Prehistoric (1200-450 B.P.), and Proto-historic (450-250 B.P). These groupings are based on changes in technology, subsistence, habitation patterns, and more that can be observed in the archaeological record. The dates associated with each time period are based on hundreds of radiocarbon dates taken from different sites across Texas.

For decades archaeologists have recognized Clovis peoples as the earliest known human cultures in Texas, arriving in the region around 11,500 years before present (B.P.). Over the last couple of decades, however, a handful of sites have shown evidence that humans were in the region even earlier. Two of the most well-known sites to produce such evidence are right here in Central Texas. The Gault Site and the Debra L. Friedken site are both located on Buttermilk Creek, north of Georgetown, and stone artifacts have been found in stratigraphic layers beneath Clovis points at both sites. At the Gault site, these stone artifacts, which show different characteristics from Clovis tools, have been dated to 21,700-16,700 B.P. Still, these early dates remain controversial for a number of reasons, and archaeologists await more evidence to determine if people were here before Clovis cultures.

In Central Texas, the Paleoindian period roughly dates from 11,500-8800 B.P. Paleoindians in Central Texas and across North America were nomadic hunters and gatherers who used atlatls with fluted spear points such as Clovis and Folsom to hunt now-extinct megafauna (like the wooly mammoth). Check out this video to see what atlatls look like and how they are used. Although paleoindians are best known for hunting megafauna, they also relied on smaller animals such as deer, turtles, and raccoons and a variety of local plants for food. These groups of people probably moved around seasonally following game and plant resources, but likely returned to the same places every year. At Kincaid Rockshelter, a Paleoindian site west of San Antonio, Clovis peoples brought more than two tons of stone from the riverbed to the rock shelter to create a paved floor. The considerable effort it must have taken to create such a lasting feature suggests that these people spent more than a few nights camping there.

The Archaic period represents a long span of time in Texas prehistory and is often subdivided into Early (8800-6000 B.P.), Middle (6000-4000 B.P.), and Late (4000-1200 B.P.) subperiods, which generally correlate with different types of stone tool assemblages. Overall, the Archaic period in Central Texas is characterized by intensified hunting and gathering of local resources, greater diversity in material culture, the use of heated rocks in cooking, and population increase.

During the Early Archaic, people mostly lived in the live oak savanna along the eastern and southern edges of the Edwards Plateau where water was more plentiful. People hunted smaller animals such as deer and turkey and likely collected a variety of nuts, seeds, tubers, and fruits available in this ecosystem. Starting in the Early Archaic, earth ovens made from large limestone rocks, plants, and dirt were used to cook various plants and animals. New kinds of stone tools such as grinding and hammering stones also appear during this time. In the Middle Archaic, people in Central Texas began to hunt bison more intensively and likely became more nomadic following the herds. The Middle Archaic also saw some of the driest conditions Central Texas has ever experienced. Plant remains from burned rock middens dating to this time show that people were increasingly using earth ovens to cook plants such as sotol that were adapted to drier environments. During the Late Archaic the climate slowly became wetter again, though earth oven use continued and even expanded during this time period. Increased variety in assemblages of artifacts across the region indicates that cultures were diversifying, possibly as a result of population increase.

The beginning of the Late Prehistoric period is marked by the introduction of the bow and arrow. Despite this new technology, hunting and foraging activities and overall lifeways appear to have stayed more or less the same between the Late Archaic and the beginning the the Late Prehistoric. Beginning around 650-700 B.P. the Toyah culture came to prominence in Central and Southern Texas. This corresponds to the time when bison herds returned to the Southern Plains, and bison bones are common at Toyah sites. Toyah material culture includes a distinctive “toolkit” of Perdiz arrow points, beveled knives, end scrapers, and drills, all of which were useful in processing bison and deer hides. The Toyah phase is also when the first pottery appears in Central Texas. Toyah peoples made simple earthenware pottery from local clays that had crushed bone added in to strengthen the vessel (this process is called “tempering”). These vessels aren’t called “Leon Plain” for nothing… They’re usually very simple designs that are most often undecorated. Unlike in other areas of Texas, such as the Caddo region in areas like Tyler and Palestine, Leon Plain vessels were strictly utilitarian and often used until they broke. Whole vessel finds are very rare, though some vessels have been recreated from the fragments (called, “sherds”) recovered at a site. Here is an example of one such re-assembled vessel from a site at Stacie Reservoir in Runnels County. While archaeologists recognize these artifacts as simply “Toyah,” in reality, these tools and subsistence strategies were probably adopted by a variety of ethnic and linguistic groups across a large area.

In North America the break between prehistoric and historic is typically defined as the time at which European and Native American cultures came into contact.